On Cosmic Horror, Abjection and Social Media, a Conversation with Nick Mamatas

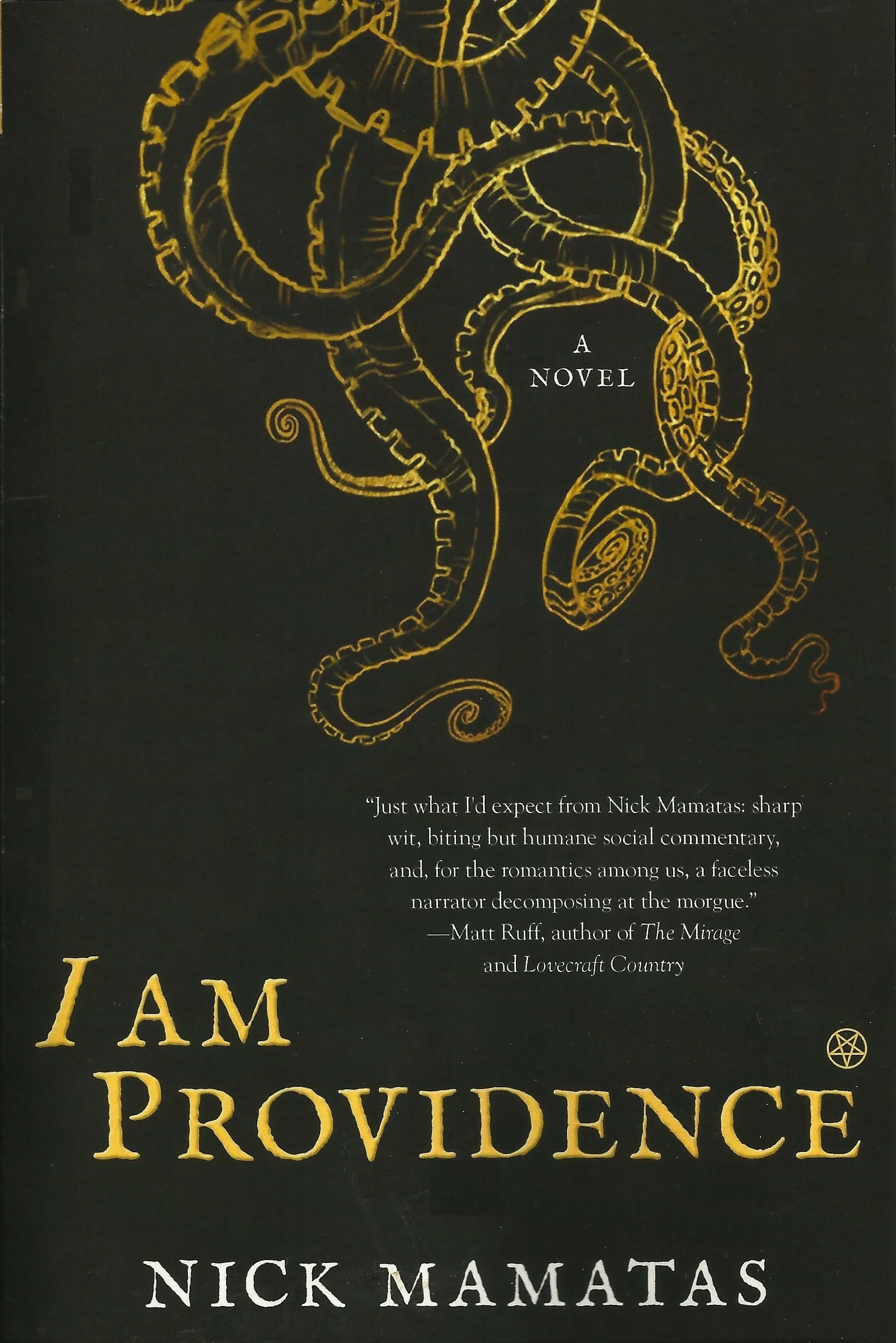

Since I'm going to review his latest novel I am Providence tomorrow for horroctober, I've invited author and publishing veteran Nick Mamatas for a chat in order to get to know him better. Some of you might know him from his fun and intense social media presence, others through his previous novels, but Nick's used not to leave anyone indifferent.

Nick graciously accepted my invitation, sat patiently through my onslaught of nerdy question and managed to help me shed light on a wide array of subject that may or may not have something to do with horroctober (you know how it is, when a conversation hits a groove). Anyway, Nick is at least as passionate as I am about literature, so read this conversation, enjoy and buy I am Providence. If you're not convinced after reading this, tune in tomorrow for my complete review of the book.

Ben: This is supposed to be about cosmic horror, but we'll get to that. Because horror isn't the first thing I felt when I started reading your latest novel I Am Providence. I began chuckling like a happy stoner every two pages. This is satire. It is brutal and uproarious, yet I can't say it's an unfair portrait of writing communities in general. Why do you think people treat their creative pursuits (and therefore themselves) with such desperate reverence?

Nick: Good question, and like most good questions there are several answers.

The first is that creative pursuits have no solid path to success—one can go to an MFA program or an art school, but one needn't. One can get an agent by sending query letters, or by attending the right events—except that query letters rarely work and the right events are obscured under a veritable mountain of wrong events that people attend instead. There's no licensing, no real apprenticeship (though plenty of people are eager to set themselves up as mentors or gurus) and in the resultant vacuum, superstitions, folklore, and a generalized belief in "drive" and "will" take over. So we end up with a lot of macho posturing, or hysterical attachment to false beliefs, or gross social climbing. That's the desperation.

The second is that in the absence of a method to achieve success, the various mentors and gurus mentioned above have to sell something else, so they sell self-expression and self-realization. To keep the suckers coming back with another check, they have to pretend that really deep work is happening on the page in these classes and workshops, even if the results are usually hackneyed and cliched. Writing becomes a pseudotherapeutic practice, which requires the pretense of seriousness. There's your reverence.

The third is that the actual truth about writing is too terrible to bear, so any other conception of what it's like will do.

Ben: I am Providence is a roman à clés. You've said before that Panossian was based on you and his co-star Colleen Danzig was based on Molly Tanzer, to whom you dedicated the novel. Correct me if I'm wrong, but I'm assuming you had an ax to grind when you started this project. There's are brutal passages to it, but there's a lot of love too. What were you trying to say with I am Providence? I've read in another interview that it was written on commission from Night Shade Books' editor but if we go even further back, what was the impulse that drove you to write a satirical roman à clés?

Nick: It's not a roman à clef—it's not a novel of real life. A roman à clef is non-fiction—that is, it depicts events that have actually occurred—overlayed with the idea of fiction; I am Providence is a murder mystery with noir and horror elements. Most of the characters, including the two you allude to, are amalgams of various people. I've had readers say, "This character is obviously X, but X isn't A, B, C!" Right, because the character actually isn't X. Same goes for the convention setting itself, which is more like Readercon crossed with the H. P. Lovecraft Film Festival and various Facebook groups and not Providence's biennial Necronomicon, which I have never attended.

Did I have an ax to grind? Sure. Satire is all about pointing out and mocking vice, after all. I had no conception of writing a satire of fandom until I received the commission from Night Shade Books, but the subject matter lends itself to satire because even straightforwardly honest depictions of the scene are comical. This review got it right: "if anything [the depiction of fandom] is a little muted--understandable, since if all the politics of even a tiny con were on full blast, there'd be no room for a murder mystery."

Ben: Another thing I wanted you input on is Lovecraftian culture, which you discuss at length in I am Providence. It is still really strong today. Inexplicably so, to some degree. I cannot, like Panossian, fathom why every horror publisher need to have their own Cthulhu-themed anthology. But I'm still very much an outsider to this culture. Why do you think this literary subculture is so strong and well-defined? The cynical answer would be that Lovecraft's extensive and well-documented mythos makes it easier and more satisfying to write stories that belong to something greater than themselves, but I'm sure there is much more to it than that. What do you think are the other factors involved in Lovecraftian culture's success?

Nick: Lovecraft's mythos (a term I always found a little portentous) is expansive, but not well-defined. Plenty of room for more that way. But it's a collection of tropes, set pieces, and themes, like any other genre or subgenre. We also have a ton of vampire novels, and a lot of literary fiction about the epiphanies arising from the anguish of a recently discovered instance of infidelity. Lovecraftian horror lends itself to the short story rather than the novel, though, and small presses can afford to put out anthologies more easily than novels—there are sixteen to twenty people promoting the anthology instead of a sole author and the stories are often paid for at a flat rate—so we end up with a lot of Lovecraft.

Certainly the organization of Lovecraftian fandom also helps in this. Becoming an anthologist gives one some aesthetic influence, and the minor power gained by handing people money. Who doesn't want to be loved? Plus, editing an anthology is easier than writing a whole book, and you still get your name on the spine. Editing an anthology for a major publisher is tricky. In addition to having a familiar-but-different theme and a Rolodex full of writers, you need to answer a question: why should we hire you to edit this instead of the people we normally work with? So, Lovecraftian anthologies in the small press are very common.

We shouldn't deny the thematic power of Lovecraftian themes. There are other reasons why there are a lot of Lovecraftian fictions and not a huge number of William Hope Hodgson pastiches out there. The themes of alienation and obliteration are compelling—we all feel somewhat like outsiders, and when we finally find a place where we're the insiders, we've accomplished this by twisting ourselves in knots. Lovecraft's work is all about that.

Ben: What do you make of contemporary cosmic horror which strays from the Lovecraftian roots of the genre? Laird Barron, T.E.D Klein, Grant Morrison's Nameless, material of this sort. Do you like it? What do you think of the genre in general, independently of its Lovecratian origins? I have this thing about finding the most terrifying horror there is and this pretty much is the only thing that moves the needle right now.

Nick: I don't know if Klein, who hasn't published new fiction since the late 1980s, is contemporary, but sure! I like anything, if it's good. I'm a quality snob, not a genre snob—I like the top 3 percent of all modes and idioms of fiction. I do think that both post-Lovecraftian fiction and weird fiction from roots other than Lovecraft tends to be better than Lovecraftian pastiches, for the obvious reason that the pastiche depends on one's memory of enjoyment being triggered, while other stuff has to provide first-order enjoyment. I think Laird Barron's stuff, especially when it combines the weird with naturalism or noir, is great. I also like Molly Tanzer, who combines sexual politics and historical fiction with weird themes, and the post-structuralist post-narrative post-everything work of Reza Negarestani. I was slow in warming up to the late Joel Lane but I recently read his collection of linked stories, Where Furnaces Burn, (three years after buying it) and actually experienced an authentic scare at the end of one story. One per book is a lot for me.

As far as being frightening goes, I think weird fiction resists visualization in a way that monster-horror (vampires, mummies, slasher-killers) don't, and thus we fill in the blanks with nameless invisible dread and fear. There are plenty of paintings and sculptures of Cthulhu, so I think that character is more suited to camp and critique at this point, but the non-visual themes Cthulhu represents are still very scary.

Ben: Speaking of monsters, you've written a zombie novel titled The Last Weekend, which I haven't read but heard great things about. One thing that came through is that it was rather light on zombies, which I thought was interesting. I've been very critical of mainstream monster horror on this site, condemning its shallow and derivative nature multiple times. What do you think monster horror has to offer audiences and why did you choose to set The Last Weekend in the midst of a zombie apocalypse?

Nick: I wrote the first bit of The Last Weekend initially on the request of R. J. Sevin, a small-press publisher looking to start a zombie fiction line that was to be called "George R. Romero Presents", but Romero didn't like any of the samples he received. I liked the book enough to finish it—it took several years to sell partially because there were way too many zombie novels being published at the time, partially because it wasn't a zombie novel. Such contradictions are common enough in publishing.

The Last Weekend is basically one of my favorite sort of novels—the bohemian kunstlerroman. In the old days, working stiffs like Colin Wilson or John Fante were able to write such things, but now one needs to have a thoroughly middle-class provenance to do so. So, zombies! Enough zombies to be interesting anyway.

Monster horror basically offers adventure, and finds its drama in problem-solving. Zombie fiction certainly has a significant audience among the survivalist community. The monster is just an obstacle. Once audiences get bored of that, the monsters change. Anne Rice shifting the locus of perspective to the vampire's point of view in the 1970s was a sea change. These days it isn't difficult to find fictional zombies with interiority, and of course the same is true with werewolves and other monsters. And thus horror transforms into romance. There are always two sides to the coin of abjection.

Ben: That's an interesting point you're raising. Is there two sides to abjection or are we just finding comfort in projecting human values and behaviors on everything? What makes monsters scary are their absence of relatable desires, isn't it? Correct me if I'm wrong, but a zombie or a vampire lover is just another form of non white Christian lover, no?

Nick: Abjection also involves elements of the self, as well as taboos of the other. For the most part the vampire lover heals abjection—Vampire Bill isn't a corpse I'm fucking, he's a good honest man, even a hero. Anyway, he only kills the bad people! (...or does he?) So in Lovecraft, we have that famous ending of "The Shadow Over Innsmouth":

I shall plan my cousin’s escape from that Canton madhouse, and together we shall go to marvel-shadowed Innsmouth. We shall swim out to that brooding reef in the sea and dive down through black abysses to Cyclopean and many-columned Y’ha-nthlei, and in that lair of the Deep Ones we shall dwell amidst wonder and glory for ever.

The abjection of the zombie is that it allows one to violate the taboo against killing your neighbors and stealing their shit, while at the same time there is an appeal to joining the zombie horde. Same with those disfigured slasher-killers in films wiping out the pretty people who get to have sex. I'm hardly the first person to note that the hardcore fans of such films tend to be pimply and awkward teen boys for whom sex is often unavailable. It's not that we relate to the monster-figure, it's that we are both alienated by the figure and see ourselves in it.

Ben: Well, I'm going to have to change subject or I'm going to start going over zombie and slashers movies obsessively and rethink my entire conception of them! Another thing I wanted to ask: I've first came across you on social media when you have very strong presence. You're not afraid to take a stand on a public platform and say out loud what everybody's muttering about. Not unlike I am Providence's co-protagonist Panossian. What do you think are the biggest ethical failings of writers and publishing professionals in the age of social media?

Nick: The biggest ethical failing is thankfully rare—people saying one thing in public, like "I don't like your work" and another thing in private, like "Please send me a story." Most failings are from people on the fringes, such as publishers with no publishing experience, or writers who don't write much but like to use social media as an outlet.

There are significant political disagreements, but that's hardly the same as an ethical failing, even if I dislike someone's politics.

Then there are just personality clashes. The dark fiction scene attracts a loud and vocal minority of people who think they can bull or tough-guy their way into some sort of success, whether aesthetic, commercial, or subcultural. And you can't. Writing and publishing isn't the same as beating someone up in a parking lot, so bumping chests for the sake of it, or doing "turf battles" is meaningless and annoying noise.

I will say that a professional lapse I often see involves issues of sex harassment and the like. Top authors and editors often get away with things at conventions and the like that in an office or factory would not be allowed, and newer writers often get confused as to what to do, and often decide to say or do nothing, or to keep negative information in their friends-circles. It's not an ethical problem, but a sign of trouble in the field as a whole. This is changing, and improving, over the past few years, but I still get to hear a few stories every year about everything from inappropriately, say, fondling the bra strap of an author you just gave an award to, to molesting an unconscious person in the middle of a party at a convention.

Ben: My experience is that it's always the most successful writers who are the nicest. Guys who really focus on their craft and can make the difference between the success of their work and who they are. It's not given to anybody though. Success does weird things to people sometimes. Which authors do you think make the best and most efficient use of their social media platforms? And what is it you think that makes them good at it?

Nick: My disappointing answer is that I don't know. I don't really follow the social media profiles of famous writers, except for personal acquaintances. And there I much prefer to see photos of their grandchildren and such rather than earnest posts about "the craft", or the "reality" of publishing, or essays about their political concerns. I do like hideous train wrecks such as Cat Marnell, though.

One reason why I skim a lot these days is to do with the old joke:

Q: "Who knows less about publishing than a midlist author?"

A: "A best-selling author!"

I used to be amazed at how fundamentally incurious so many writers and even publishers are about how things actually work in publishing as a whole. If it's not in their experience, or is something new, or something old for that matter, they just stop caring and stop thinking. In the field of science fiction, fantasy, and horror, there is a lot of good "Publishing 101"-style information out there, but people frequently confuse the part for the whole, and have no interest in learning about Publishing 102. My day job is in publishing, so I have a broader perspective than most, so I just don't find some new revelation like "I don't like it when my books are returned!" to be amazing.

Ben: I'm torn on that because I came to really understand hermit writers who focus solely on the quality of their work instead of desperately mingling hoping it will get them anywhere, but yeah, I understand that publishing is a business and that it's easy to blame others if you don't take your responsibilities as an artist and educate yourself about what's putting food on the table. It can quickly become a shit show on social media because everybody is too busy venting to treat it as a professional space. Anyway, back to I am Providence before I let you leave. I've really enjoyed the novel and I find there is more than satire to it, which is not always easy to get from the reviews. I thought the Agatha Christie mystery was a nice contrast in nature with the Lovecraftian themes and commentary and it really make the book come to life. It's original, doesn't take itself seriously and manages to make a good point about fan culture. What kind of reactions did you get in general from writing community people and random readers alike?

Nick: So far the response has been generally positive, and the book was reprinted three weeks after release—it's by far my most successful novel. If I have to sum up the responses, it depends on demographics:

a. women are somewhat more likely to say that the depiction of fandom and conventions in the novel is accurate, while men tend to think I was being unfair or unkind somehow. This isn't a strict gender split, just a tendency.

b. horror fans/reviewers are likely to call it a fun, even light, read. Science fiction fans/reviewers read the book as extremely dark, "a novel of horridness" as one reviewer put it.

c. some are disappointed that the book is only a murder mystery; without supernatural or a splash of cosmic horror or a monster, it doesn't feel as weighty. Others...dare I say it? Others read the book more thoroughly and see all that stuff in it.

I can't complain too much; I Am Providence sold more copies on the week it shipped than my 2012 novel Bullettime in the four years it's been out.

Ben: Anything else you want to say or plug before we leave? Go nuts!

Nick: My 2013 crime novel Love Is the Law is still on sale, and only $7.99!

Over at my day job, I co-edited an anthology of supernatural and science fictional crime stories, Hanzai Japan! *

Check those out next!

* I've reviewed the anthology last fall, for those interested - Ben